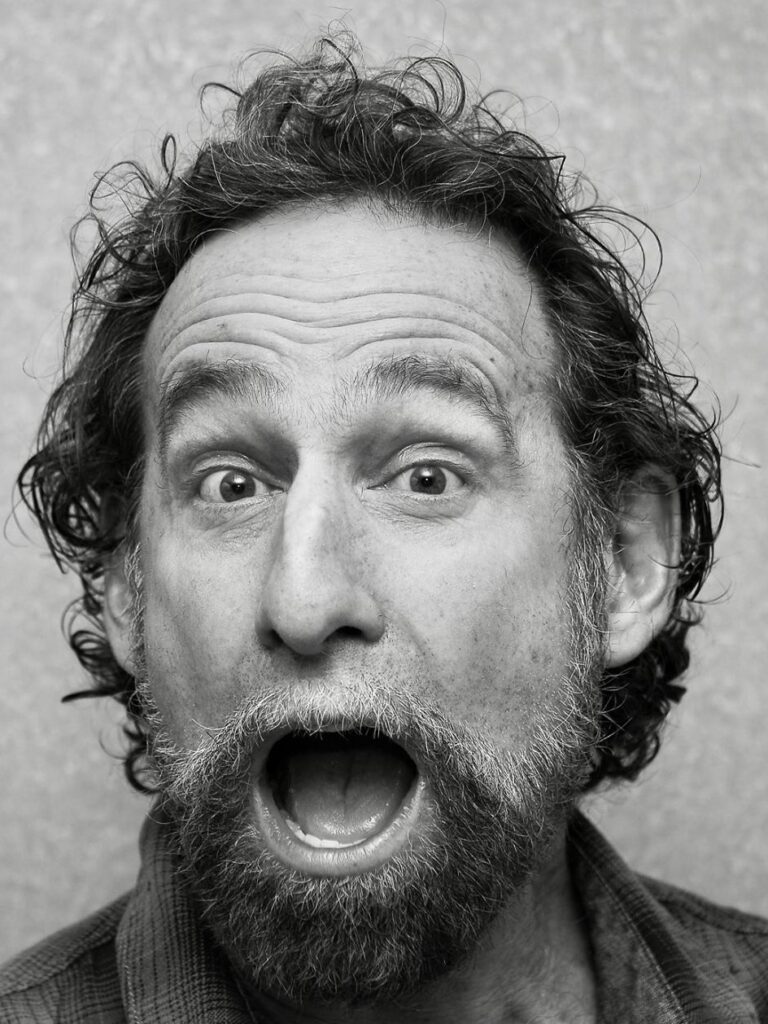

About Jeremy Sherman

Growing up, I was a slow learner. I had a hard and anxious time getting my bearings. But I was lucky. Through circumstances of birth, I could afford to try out many of the rides in life’s amusement park before settling down.

I’ve been an outhouse pumper, advisor to the Army Intelligence College, plumber, foundation director, elected elder at the world’s largest hippy commune, advisor on drug discovery for big pharma, water engineer in rural Guatemala, public policy director for a multinational green corporation, barn builder in the deep south, founder/director of a national grassroots environmental lobbying campaign, husband, college teacher across the social sciences, rural fire chief, aspiring orchestral bassoonist, refrigeration repairman, jazz bass player/vocalist, psychology blogger/vlogger, father of three, one a mentally ill drug addict. Lots of lucky, learning rides.

Twenty-five years ago, as I was coming out of a midlife crisis, I fell in with the Harvard/Berkeley neuroscientist/biological anthropologist Terrence Deacon, a lab scientist addressing questions so huge most scientists don’t notice them. At Harvard, they described him as a genius and a saint, a saint because he was unassuming, and happy to explore with anyone who was trying to think carefully about these huge questions. Though I’m no lab scientist, we’ve been working closely ever since.

His big questions are simple though unfamiliar. The big one we’ve worked on together is what selves and trying are and how they emerge within nothing but chemistry. See, there’s a gaping hole in the middle of science. Selves and trying are impermissible concepts in the physical sciences but unavoidable in the life sciences.

For all science has uncovered we’ve lacked an explanation that bridges that gap between physics and life. Evolution and DNA don’t, though biologists often pretend they do. Darwin knew he didn’t explain the struggle for existence. DNA is a molecule, not a self trying to do anything.

Deacon has a no-smoke-and-mirrors, no philosophical handwaving, no quantum consciousness, strictly physical scientific explanation for how selves making functional interpretive effort could ever emerge within nothing but chemistry.

Deacon’s explanation isn’t complicated. It can’t be. Selves and effort must have started simpler –way simpler than the simplest known organism. Not complicated, just unfamiliar. It’s funny. We’re all a little self-obsessed trying to figure out what to try to do. Yet almost nobody stops to wonder what selves and trying are.

Terry writes dense academic prose. With Terry, I work on the theories but also on making them more accessible, intuitive and relevant. Advanced ideas for beginners.

Claiming to have a solution to a problem as old as human curiosity, I can seem like a crackpot with some grand fringe theory. Could be. If you join science’s search party, there’s a good chance you won’t be the one who finds the answer. You accept the possibility that you’ll have spent your whole life barking up the wrong tree. Still, of all the researchers I read, and I read a lot of them, I don’t find a better physical explanation for selves and trying or any flaws in our approach. I’ll keep looking. Of course, you’ll make up your own mind about whether I’m a crackpot.

Looking back, I get the arc of my lucky life. I was really self-conscious and anxious about what I should try to do. I tried lots of ideas to gain peace of mind. A little before meeting Terry, I noticed a shift in me. I turned my attention from what’s wrong with me to what’s up with us and away from abstract spirituality to science which I see as a campaign to find natural explanations for all natural phenomena. I stopped shopping for a consoling interpretation and got interested in how we shop among interpretations and thus, the natural history of wising up. Not that I assume we humans are wising up necessarily.

That’s the grave part of my arc of interests. I think of us humans as a precarious evolutionary experiment in sustainability. With language and technology, we have the potential to be stewards of our own survival. Language makes us way more visionary and alert to the big picture than other critters, but also more delusional and denialist.

I think of us humans as like mammals who dropped acid a couple of minutes before midnight if you scrunched the universe’s history down to one year. Here we all are a few minutes later tripping balls and driving heavy equipment. It’s dire but also slapstick.

Terry is a nerd. I’m more hotheaded by nature but cooling under his influence. I’m with Terry on how to approach the human condition. I want to study it as neutrally as possible. I don’t want my advocacy to influence my analysis. I’m not out to provide reassurance, not even the reassurance of the hard-headed tough, badass scientific realist. I want my analysis to inform my advocacy. I’m out to make my best guesses about reality relevant. I figure we were dropped down into reality and can use some of our time here to figure out what’s going on, which, lacking language, no other critters can do.

These days, a lot of my attention is devoted to psychoproctology. I study how humans can become assholes or their plural, cults. I think of assholery as a bigger problem than nukes or climate crisis, huge though they are. I figure we’ll never be able to address those other huge problems if we can’t put a leash on our tendency toward assholery. It’s that grave.

Psychoproctology is a light name for a deadly serious subject. It has to be light. It’s dangerous to take yourself seriously in psychoproctology. The worst assholes in history were absolutely sure that they were experts on who was an asshole: Anyone and everyone who got in their way.

Psychoproctology is about diagnosing, treating and preventing assholery. In other words, what’s the most objective way to distinguish between assholes and non-assholes, how to deal with them, and how to prevent ourselves from becoming like them. It’s constraint-based moral philosophy: Be whatever, but don’t be an asshole. For that, you have to get very careful about distinguishing between assholes and the vast variety of decent folks. A butthead can’t just be whomever we happen to butt heads with.

All of my research, from the origins of selves and trying through the evolution of language and how it changes us to my research on a-holes has made me an ironist fallibilist. Fallibilism is the recognition that our tries can fail. Yoda was motivating but wrong. There’s only try. Trying is all life has ever done. My fallibilist motto is no matter how confident I am in a bet, I remain still more confident that it is a bet.

Irony is my recognition that trying in our iffy world, we can never escape the possibility that our good bets will turn out bad and vice versa. I find it all dire, slapstick, and astonishing. I’m lucky I get to spend all day working playing and savoring it.